Introduction

In our project, we explore the question: How can we learn together to better understand local climate change?

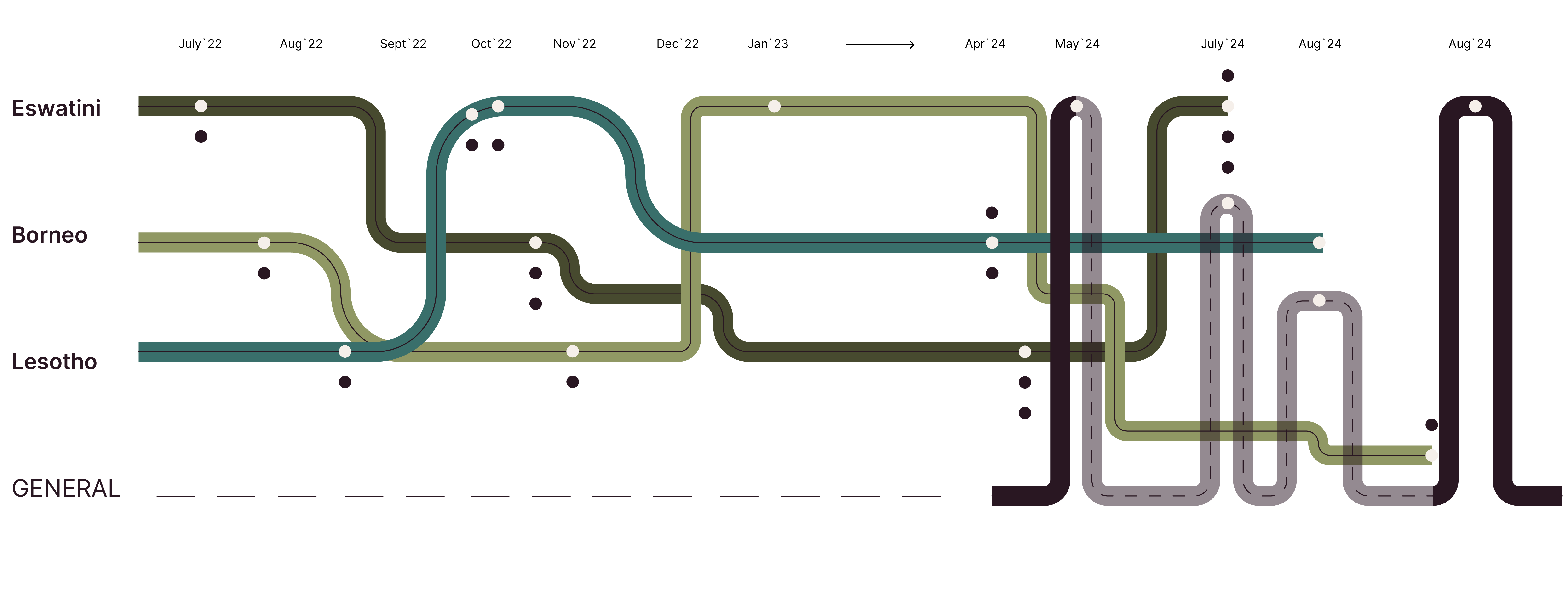

Over the past two years, we worked with various Indigenous communities around the world to create Indigenous Climate Observatories. We established seven different observatories:

- Two in Borneo, Malaysia, focusing on river and forest connections.

- Three in Eswatini, focusing on biodiversity.

- Two in Lesotho, focusing on weather patterns.

These observatories brought together researchers, climate and biodiversity experts, and Indigenous communities who experience the impacts of climate change daily. Each observatory is deeply connected to its specific location, addressing themes relevant to that area.

We focus on understanding indicators of change: how can we recognize changes, and what signs do, or could communities use to observe these changes? Each Indigenous Climate Observatory uniquely adapted to its local context, bringing together local communities, their concerns, and their interactions with researchers. This approach introduces specific indicators of change around for the communities’ relevant themes, making each observatory distinct.

Background

Indigenous communities have a special connection to their environment, which means they notice changes in the local climate that others might miss. This insight can be incredibly valuable in understanding climate change and helping these communities act in their own unique ways.

In Indigenous worldviews, humans are just one part of a larger, interconnected world. There is no separation between nature and culture. Everything in the world is seen as alive, and everything has its place. Because many Indigenous communities live closely with the land, they are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of biodiversity loss. However, their deep local knowledge about their environment is crucial for understanding climate change and its effects. Unfortunately, this valuable knowledge is often overlooked in climate research and policymaking.

Researchers like Turner and Clifton (2009) believe that empowering Indigenous communities to use their traditional knowledge is essential for them to adapt successfully to local climate impacts. However, as Nightingale and others (2020) have pointed out, the knowledge produced about climate change often doesn’t connect with traditional local knowledge and other ways of understanding, turning it into mere data instead of a practical foundation for local action.

Objectives

In our project, we see great potential in exploring ways to “work knowledges together,” a concept introduced by Verran (1998). This means we respectfully learn together and accept diverse knowledge systems as equal.

Participatory Design calls this a pluriversal approach to design, which has been popularized by scholars like Escobar (2018) and Mignolo (2012). A pluriverse embraces the idea that multiple ways of understanding the world can coexist. This approach is inspired by the Indigenous Zapatista movement, which envisions a “world in which many worlds fit,” celebrating diversity and differences.

To facilitate the exchange of knowledge systems, we recognize that knowledge is power. Those who share their knowledge should remain in control of the process, and we must take special care to avoid harming already vulnerable communities. The way we shape the Indigenous Climate Observatories demonstrates how we “work knowledges together.”

Our project aims to understand what Indigenous Climate Observatories can look like and how we can bring together different forms of knowledge in respectful ways, within them.

Approach

In our project, we have set up seven Indigenous Climate Observatories where both Indigenous and scientific climate indicators are brought together. These observatories aim to create a respectful space where different ways of understanding climate change are seen as equal.

The observatories are designed to be community-led and address local climate issues that affect the daily lives and livelihoods of Indigenous communities. They also aim to support these communities in adapting to local climate changes.

We use a Respectful Design approach, inspired by the ideas of Indigenous scholar Norman Sheehan. This approach recognizes that all life forms are interconnected and exist in relation to one another. It focuses on respecting the ways of local communities and ensuring that their benefit is central to everything we do together. It also provides ways to think about bringing different worldviews together and is sensitive to the perspectives of local Indigenous communities.

Respectful Design can be understood as a variation of community-led Participatory Design. It focuses on:

- Promoting mutual learning and creating a “world in which many worlds fit,” celebrating diversity and differences.

- Establishing spaces for discussing possible, plausible, probable, and preferable futures among different stakeholders and domains.

- Learning by doing, where making things helps support mutual learning as making helps to make issues concrete and negotiable.

As we talk about Climate Observatories, we can also position our approach as an ‘experimental’ citizen science project (which was introduced as a concept by Danielsen and others (2018)). Unlike most citizen science projects, we involve citizens in all aspects of environmental assessment and monitoring, including program design, data interpretation, and using the results for decision-making and action. What makes our approach to citizen science unique is the artistic ways of working that are central in establishing the program design, the data collection and interpretation.

Design Process

Our process includes several steps: Exploring local change indicators. Creating hopeful expressions regarding these indicators. Recording changes through these indicators. Reflecting on what these changes mean and considering actions to counteract them. We also have moments where we introduce our collaborative learnings to a wider audience.

Though we do not take a scientific approach to climate change research, we still use some more scientific terms to define the different stages of the process. However, the process model, is based on indigenous process, that are often circular, rather than linear. It is shaped as a spiral, growing into something specific, based on the interactions within the specific observatory. This means that all the processes are different, but that in each, each phase informs the next. Roughly, it follows the steps below, often in this order, but sometimes not. The starting point might differ depending on the input of the community.

- ‘Defining’ (scientific & indigenous) climate change indicators – an open exploration using design seeds, to find indicators, to explore what ‘data’ is, to define what ‘measuring’ means.

- ‘Measuring’ with indicators and collecting ‘data’ (both scientific & Indigenous)

- ‘Validating’ how do we understand the data? How does it compare and contrast? Talking between, with different knowledges.

- ‘Futuring’ understanding what these climate observations can mean to plan future action for/by and within the community

Where we are now

This project started through support through a project grant from the Crafoord Foundation. In this project we were able to set up the collaborations with the local researchers and communities and other stakeholders which resulted in 7 different observatories. As mentioned before, we take a participatory design approach which means that those who the design is for are central in shaping where the project goes. This means that this project was also a means to explore what future collaborations should focus on. In each of the different settings will we have continued or new observatory efforts. So stay up to date by checking in here or by sending a message to Lizette Reitsma.

We also are in the processes of starting some new collaborations. Hopefully soon more information about this!

Project Timeline